Like many geeks, I like theories and laws. In fact, I have my own law: Harding’s Water Principle. Well, I’m advancing another theory that could become a law or principle, the Supermodel Software Theory.

I’ve spent the last 25 years of my life developing software. Some of it really bad, most of it simply average, and I’ve had the pleasure to work on very few extraordinary projects. I’ve been engaged in these projects as an architect, product manager, systems analyst, software developer, QA engineer, technical lead, manager, manager of managers, and executive. So I’ve seen the whole lifecycle, multiple times from multiple different perspectives.

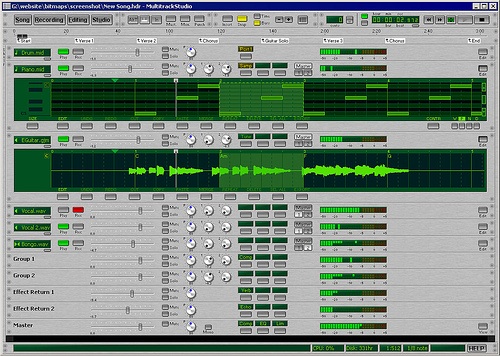

Here’s what I’ve learned: Great software has three attributes; aesthetics, usability, and utility in a specific mixture which we’ll discuss in depth. Aesthetics are what you’d expect, is the software visually appealing and inviting. Usability covers how the human interacts with the software, is it easy to learn? To use? Do I want to use it? And utility covers the spectrum of functionality, does the software do what I need it to do to be useful?

Average software tends to be designed and developed by people who are content to benchmark. Go to any airline’s website, they all look the same, have the same features/functions, and generally behave in the same way. They have utility in common and largely compete in that arena (which is a good thing when you want to book a ticket, check flight status, request an upgrade, etc.) But, do you love to use the software? Do you want to go back? Or do you often dread fighting it to get done what you’ve set out to accomplish? What tends to be wrong is the over focus on the utility, features and functions everyone else has. Consequently there is an under investment/focus on aesthetics and usability and a lack of discipline in the selection of the features that truly matter to the user.

Bad software tends to be hugely unbalanced across aesthetics, usability, and utility. We can all think of great looking software that is useless, highly helpful software that is useless, and utilitarian software that is useless. Often, very popular software fits into these categories, for example, Dbase III (I’m dating myself by using this example) got the mix right, Dbase IV, messed it up royally. Consequently, Foxbase and then MS Access were able to take their lunch money.

Great software is like the rarest of supermodels; those people with incredible looks, a fantastic personality, and high learning agility. Why does this matter you might ask? For humans, if something looks good, it gets the benefit of the doubt (aesthetics.) That’s not enough to sustain interest, but is often enough to open the door. Now, if that supermodel has a great personality (usability) that goes along with their inherent good looks, you’re on to a winner. Why? Because ugly and mean are nearly impossible traits to fix. Finally, if we discover that our supermodel has some useful skills, but even more importantly, is willing and able to acquire new skills, we’re going to be very, very happy and we will attempt to form a long-term relationship with that person.

It’s worth talking about learning agility. Like ugly and mean, stupid is nearly impossible to fix. Ignorance can be addressed. This learning agility – the ability to transform ignorance into knowlege – is an analog to the utility layer. How we do this is to focus on a small subset of things where we can excel. Over time, by doing this consistently, the base of knowledge (or utility of software, or feature breadth if you will) grows ever more complete and compelling. But the important part is to select one area where the software can be truly excellent. In the utility portion of software development, the industry at large has little discipline, we go overboard, trying to get every feature/function under the sun stuffed into the software. While that can be intellectually interesting, it’s not particularly helpful.

The theory is: Like a supermodel, it’s essential to have pretty, nice, basic and focused competence, and learning agility in software because people are predisposed to accept the possibility of improvement when they enjoy the product. The order is vital, because people are less tolerant of highly utilitarian software lacking looks and personality (we may hope we’re better than that, but we’re not. Remember, ugly, mean, and stupid are forever. Ignorance can be cured.)

So, using the theory, the recipe for building great software is pretty straight forward. Design a compelling user interface first which ideally contains the core feature where your software will be truly excellent. Resist the urge to benchmark. Test your concept early and often with your users and adjust as quickly as possible. It’s better to be pretty, with a good personality, and only truly excellent across a narrow area to start. Once in the market, identify the next most vital utility in a narrow band, get that right and release it. Rinse and repeat as necessary. Now, does this guarantee extraordinary software? No, it doesn’t. But if this process is followed, the chance that your software will be great increases dramatically.

So, the next time you or your company plan to undertake a software project, dust off this theory and try it. Remember, the choice is yours. Escape the tyranny of benchmarking, resist the urge to load down the project with hundreds of features, and find a nice, attractive, project with high learning agility to bring home to meet the family. You’ll be glad you did…

Another benefit of a fast and frequent go-to-market strategy is valuation and a gentler and continuous improvement of the product. Usage determines value in a market-driven economy. We want our supermodel to be fit too, right? It looks like we need to talk a lot to our customers and ensure business is engaged with software development. I guess we need our customers to view a lot of profiles and in the metaphor makes our endeavor a talent company for several models, probably of both genders.

I’ve also come to believe in this; it’s what I call the narrative theory of software. In the early years, this came disguised as the “great demo” theory, one we’ve likely all seen in this business — the belief that it matter not whether the software works, as long as it was a compelling demo experience. While I’ve certainly seen plenty of software fall flat after failing to get past a great demo, the demo-centric-design is a necessary, but not sufficient, component of the “super-model” software approach. What both the demo-centric and the narrative centric theory share is a sense of progression and transformation that takes place in the mind of the user; the best software excels in the choreography of transformation. If you know what point B is, you’re more likely to get there from point A; but if you can make it pleasing for your user to get from A to B, then your efforts have passed a key test.

I think what kills software that starts with the potential to be a supermodel is burdening it with more than it’s fair share — as we’ve seen with supermodels whom we ask to also be politicians, actresses/actors, musicians, and intellectuals. They can’t do it all (What if Naomi Campbell had to defeat a filibuster?), nor should we expect them to. Humility in the face of the user’s journey from A to B should dictate a cleaner, more focused approach. Without it? The resulting litany of mediocre software is endless.

Just a curiousity question – would you say this is true for all software types, or would you say it’s predominantly true for non technical experts using off the shelf software packages? I’m thinking of all the IT code crawlers and the Linux developers in terms of what they’d consider aesthetic and utilitarian vs. my mom. Or would you adjust the definition of what utility/aesthetics/agility mean by the intended audience of the software?

Lynn, I would adjust by audience what great aesthetics and usability mean. As you rightly point out, there isn’t a single definition.

The supermodel analogy works for me in the “I’ll know one when I see one,” type of way. It would apply across every audience, though clearly the individual audiences would differ on their opinions.

I had a boss who used to have the Brad Pitt theory. Essentially: I can aspire to be Brad Pitt all year, but essentially it’s an unattainable goal. Can you really “design” a supermodel, or does one just happen as a freak of nature?

I don’t know that you can guarantee success Jim, but I do know that if you get the ingredients wrong you disqualify the desired outcome. If you get them right, you’ve got a chance….

This resonates with something I see a lot in software development.

I agree that you definitely can’t guarantee your project will be a ‘supermodel’ but you can guarantee it won’t be if you set out with your standards and goals set too low.

Pragmatism is fine but I too often see that as the default state and from inception projects aiming to be ‘pretty good’ rather than aiming to be ‘great’.

We need more people aiming for greatness, not fewer.

We need more responsibility being taken by people that make the software to look at themselves as professional craftsmen willing to say ‘no, you can’t have that, it would make the app bad for these 5 reasons…. I don’t tell you how to budget for the upcoming year but I WILL tell you how to develop software. And if you want someone that won’t, please employ someone cheaper who will blindly do what you say.’

I might have gone off on a little rant there…

please drop my tags in the above post. as I’m a doofus